Opera Saratoga opened a brilliant staging by Lawrence Edelson of Marc Blitzstein’s The Cradle Will Rock on 9 July 2017 in Saratoga Springs. The production alone is reason enough to go. But the chance to be a part of the show’s inspiring, fascinating, distillation of American Music Theater History is something that anyone who loves either music theater or opera (or, like me both—and especially the intersection between the two) should witness. For the first time since 1960, the show made famous by being shut down temporarily by the Feds and performed from the house with the composer onstage at the piano is being performed with the composer’s own orchestrations. If the media can be the message, sometimes the venue is the vision.

At the age of seven, small and awestruck in a plush red velvet seat in Uiehlein Concert Hall in Milwaukee, I was mesmerized by the conductor, Kenneth Schermerhorn. He was strikingly handsome, and athletic. He was charismatic, and when he raised his arms it was easy to imagine that he was celebrating the Eucharist. In fact, he radiated the authority of a minister, but his back was to us, and there was sensuality in his movements when he cued the glittering array of brass instruments, sumptuous strings, and bird-like woodwinds that stirred me. But he was more than a shepherd guiding a flock; he was the orchestra’s sovereign—he was the only one who literally knew the score, and the congregation read only their assigned lines. I didn’t possess then the language to put words to what I was thinking and feeling, but I understand now that what I was experiencing was the intersection of aesthetic, political, psychological, and spiritual forces that constitute performance at the highest level. It blew my mind. The concert hall was like a cathedral, the audience like a congregation, and the communion—for me, at least—entirely spiritual.

In retrospect, I’m not surprised that—sitting there trying to decide which of the many instruments on stage I would most like to play—I decided to become a composer first and a performer second. It was because my father had unintentionally taught me that although Power can compel, it does not last; my mother had by example taught me that Authority can inspire, and therefore last forever. Like Love, Authority must be earned. Every time a new piece of music is read for the first time the composer starts with all the Power and no Authority. If the music inspires and moves the performers, then the composer’s Authority grows. If it does not, well, as Virgil Thomson, whose game-changing Four Saints in Three Acts premiered in 1927, once told me, “Don’t worry about withdrawing pieces, baby; they have a way of withdrawing themselves.”

Never has there been a composer who so comprehensively manifested both in life and work the ironic union of opposites than Marc Blitzstein. Son of a wealthy banker, he received a full scholarship to study piano at no less than the prestigious Curtis Institute of Music; but he wanted to compose. Believing in “art for art’s sake,” this tonal composer traveled to Europe and studied with Arnold Schoenberg, dean of modernist atonal composers. Homosexual, he married a woman whose translations of Brecht introduced him to not just his theories on theater, but his politics, and the socially conscious Weimar Composers—Hans Eisler, Kurt Weill, and Paul Hindemith. By 1938, his first “commercial” music-theater work, which was really a numbers opera, The Cradle Will Rock’s "second act" opener was a self-lacerating duet called “Art for Art’s Sake” in which a painter and musician do, well, what Blitzstein was taught to do during Tea Time at Curtis. The apotheosis of this transit? Composing, for the Metropolitan Opera Sacco and Vanzetti, a grand opera about two humble immigrant anarchists convicted and executed for a crime for a crime they may not have committed. Had there been no Blitzstein, there would have been no “radical chic” at the Dakota for Bernstein, no link from Eisler to Bernstein, by way of Boulanger. And we’d all be deprived of the most vital branch of the American lyric theater’s stream.

When Olive Stanton (who was not the neophyte that myth and Tim Robbins in his lovely film paint her as having been) stood up on cue in the audience in 1937 there was Method (though Welles famously hated the Method) in the madness, magic in the moment. “I’m checkin’ home now,” she sang, and our hearts are meant to rush to her, knowing full well that she’s all artifice, Blitzstein’s throaty Lenya. The sarcastic earnestness of Blitzstein’s lyrics embodies his own inner-conflicts. For example, instead of allowing us to really care for Moll when she asks Andy behind the lunch counter for “Coffee and” Blitzstein crafted a joke: “Coffee and … Andy.” His come-hither dramaturgy is smacked down by a Brechtian, distance-making pun. (Similarly, when Paul Muldoon and I wrote the opera Bandanna together, I encouraged him to indulge his penchant for Oxonian wordplay, even though the characters would, by and large, not have expressed themselves thus, and his hand, as an author, would constantly push the audience away as the music pulled them in.) Blitzstein penned broad caricatures not meant to engage us emotionally, yet, in Moll—on whom I modelled the character of Doll in my own Vera of Las Vegas for this reason, and who is portrayed movingly by Ginger Costa-Jackson in this production—he created for the audience a compassionate avatar.

In the Druggist—evocatively sung with vocal slice and clear diction by Keith Jameson in this production—Blitzstein has clearly crafted a Lear figure, but gives his character no satisfactory payoff. We’re meant to be stirred by Larry Forman’s moral authority, yet we meet him two-thirds of the way through the show and, deprived of the personal magnetism of a Jerry Orbach, the role falls flat—Christopher Burchett is a forceful, slightly bemused, ultimately charismatic Larry in this production. Who do we hear about all night long? Mister Mister. He’s more fun to spend time with, after all. We’re not meant to care about Larry. As Everyman, he’s the manifestation of our righteous indignation. Franklin Roosevelt, in his 1933 Inaugural, had put it plainly: “The only thing we have to fear … is fear itself.” We don’t need to know Larry until he, by showing that he is not afraid of Mister Mister, deprives the Trump-ian Monster of his Power by revealing that he has no Authority.

Bernstein told me that Marc had intended to respect “the third wall” up until the offstage trumpets at the end. Only a year after that fateful night in 1937 when Welles and Blitzstein were compelled by circumstance to eliminate the third wall, Thornton Wilder would run with it, eliminating it without fuss entirely in the shape of Our Town’s Stage Manager. That in 1935-36 the season Porgy and Bess opened on Broadway, Blitzstein would compose an opera (that is a musical that is an opera—it all begins to feel a bit like the reveal in Chinatown: “My sister, my daughter”) that bites the hands of the people who most underwrite opera is unsurprising—I write operas to speak Truth to Power, too. But that he would score it for an orchestra in the pit and embrace the idea of the extravagant, Welles-designed crystal palace set for the 1937 staging is deeply ironic. The orchestra is, after all, an artistic manifestation of 18th century European society, everyone playing their part, only the benign tyrant on the podium knowing the score. Welles’ masterstroke of an insight (he was, above all, a genius of an editor, dramaturge, and adaptor of found material) was to understand that the Authority, the Authenticity, of the piece would be damn-near apotheotic if the composer was alone onstage at the piano, calling the scenes out as though at a backer’s audition—simultaneously the audience’s and backers’ supplicant and god.

In the theater, there are strict protocols for who may speak to whom during production. I’m well-versed in them and have, in the past, relied on them during moments of high-stress, when one is taking artistic risks and feeling particularly exposed. As a Curtis grad (and composer / conductor / librettist / director of nine operas) who, like fellow-alums Blitzstein and Bernstein, was presumeably schooled during weekly Tea Time on “how to behave” in a Green Room, and who “plays the clarinet in the room, not the one in his head,” I sat in the house during the orchestra dress rehearsal and took the piece’s temperature as a seasoned peer. The forces at play during the performance were absolutely incredible: I could feel the grinding of gears as the (decadent?) European Power Structure Paradigm of the Orchestra (with a capital “O” onstage, not nine feet below in a pit, because of the practicalities of this particular theater) and the Maestro both served and upstaged the document. I thought of the great actor / writer / director Howard Da Silva, veteran of the Blacklist and the original production of Cradle, director of several revivals, including the 1947 one conducted by Bernstein. Suspension of Disbelief was never in the cards, of course; but this was different.

When Bernstein conducted that 1948 revival—the first to use Blitzstein’s original orchestrations—he was given a few lines of dialogue, thereby creating what John Mauceri referred to as “provenance” for his own uttering of the same lines last night while conducting the orchestra dress rehearsal of Opera Saratoga’s production—the first to use Blitzstein’s orchestrations since the 1960 New York City Opera radio broadcast featuring Tammy Grimes conducted by Lehman Engel. When we discussed it, Opera Saratoga’s artistic and general director Larry Edelson elaborated,

“I wanted to give Cradle a fully staged presentation, as so often it is done semi-staged or in concert. My one nod to the original circumstances of the premiere is to have Maestro serve as the Clerk. This has become a part of the tradition of the piece, and with our theater and having the orchestra on stage behind the set, I felt we could honor that part of the piece’s history while still maintaining the through line of a fully staged production. (If our theater had a pit, I would likely have made a different choice.) In the libretto, it actually says that Blitzstein played the roles of Clerk, Reporter and Professor Mamie on Dec. 5, 1937 when it opened at the Mercury Theatre!”

Blitzstein, a man of the theater, would have known himself well-served by a maestro who respected and protected the integrity of his notated document as expertly as did Mauceri. (His Decca recording of Blitzstein’s Regina, with Angelina Reaux, Samuel Ramey, and Katherine Ciesinsky is one of my treasured touchstones as a composer.) But would Blitzstein have assigned Maestro lines of dialogue? Did he want to have that conversation? It’s a daring idea, and one I’ve seen put into play in a dozen black box operas and shows over the years. In the context of the Opera Saratoga production, the orchestra and Mauceri onstage, albeit behind the crafty single-piece set painted Rust-Oleum burnt red to match the interior of the theater, it strongly underscored the fascinating Power versus Authority dynamics at play between Maestro and Composer, Maestro and Director, Orchestra and Cast, Document and Production.

In fact, to my ears, the presence of the orchestra in Opera Saratoga’s production serves as the “dramaturgical nuclear reactor” that powered the document—not the least because Edelson’s staging expertly counterpoints with specific choreography and stage a dozen orchestrational flourishes. That Blitzstein’s orchestrations—suave European Weill-isms and an instrumentation similar to Weill’s Mahagonny Songspiel—married to sure-fire American commercial-scoring tricks from the 30s by way of vaudeville (read: those wonderful Paramount circuit orchestras all playing Charlie Chaplin’s scores) and tartly Stravinsky-esque doublings by way of Boulanger and Copland. Indeed, biographer Howard Pollack (whose recent Blitzstein biography eclipses even Eric Gordon’s superb Mark the Music) underlined for me just why the orchestrational similarities between Blitzstein and the Brecht-collaborator Weill are so important: “the novel use of accordion, guitar, and Hawaiian guitar ... all enhance the Brechtian distancing effects found in the work proper.” The Eisler-iana is there, too, of course; but the effect is not as chiaroscuro as the European; Blitzstein’s scoring is more fun, and a bit sexier.

Maurice Abravanel told me at Tanglewood that, when he conducted the first Broadway production of Weill’s Street Scene in 1946, he agitated for a “scrappier” orchestral sound, but that Weill insisted that American Broadway audiences wanted “sumptuous strings, plush tuttis.” There are few of those in Blitzstein’s Cradle orchestration—it is quirky, original, edgy, and far more like Little Threepenny Music than a commercial score. Throughout, as one might expect, the effects that Hershey Kay and Sid Ramin would in a few years craft with Bernstein for On the Town, and West Side Story are nascent. In Blitzstein, however, they all are dropped within a few measures, the point having been made. During one sequence for Missus Mister, Blitzstein uses a single maraca to limn what Bernstein would have fleshed out into a fully-scored rhumba; during another, a tender duet for the doomed Polish couple, Blitzstein adroitly adds a dash of menace in a bass drum, stalking away below like a heavy; in another passage, scored for low brass, as Bugs threatens Druggist, Nino Rota’s “Corleone Theme” from his 70s score for The Godfather is thrillingly presaged.

“As the director,” pointed out Edelson, “I didn’t feel the impulse to update the piece or to view it through a particularly 2017 lens, because the piece, written as allegory, speaks to me as if it were written yesterday. I certainly added a few things in the staging to highlight themes that resonated strongly with me, but I also trust the audience. I wanted to set up Blitzstein’s ‘Steeltown, USA’ so that the audience could have their own response to the material—not to force a response on them.”

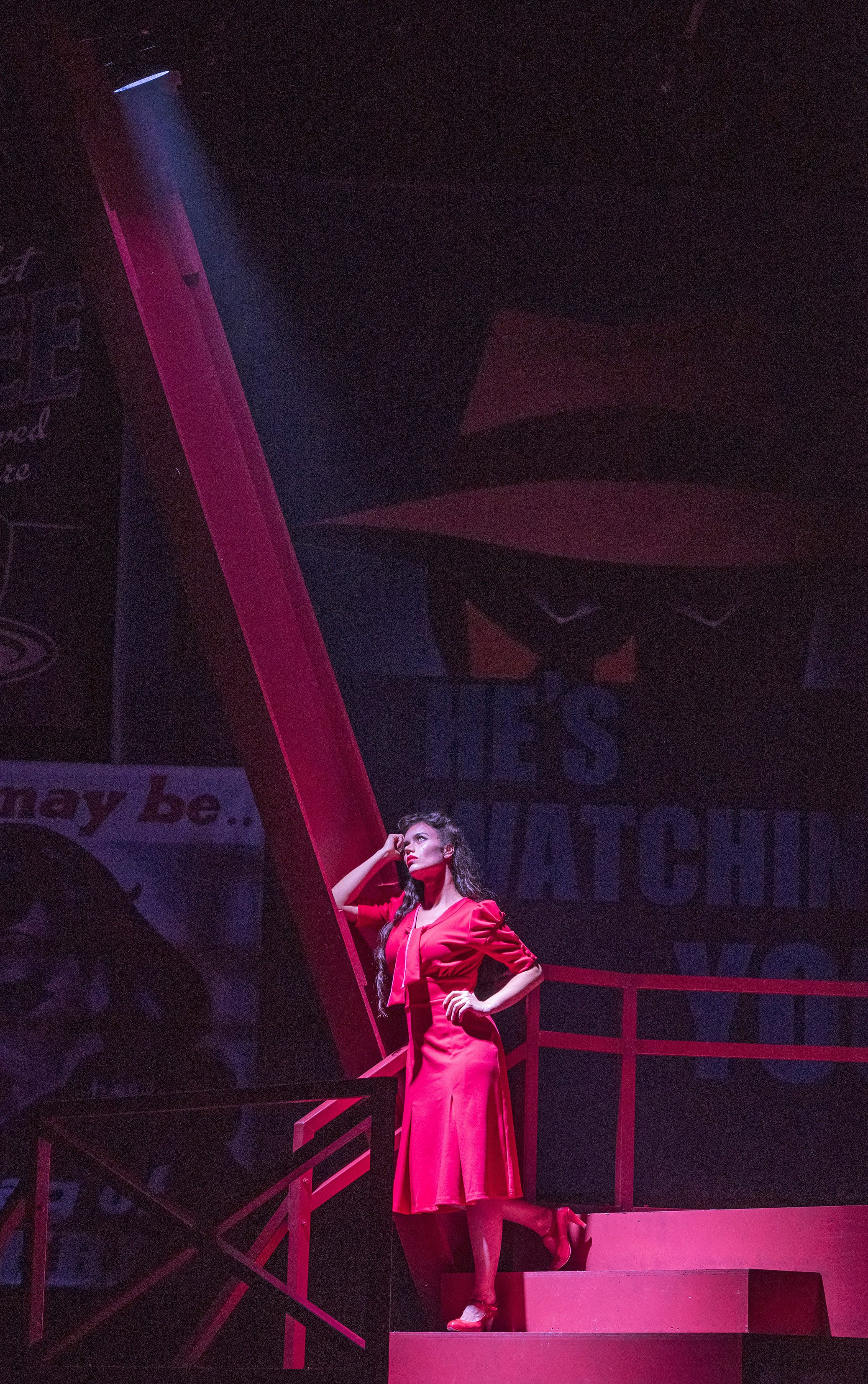

This is evident throughout the production. One of Edelson’s crucial, droll grace notes is the surprise appearance on the feet of the members of the Liberty Committee of stylish red pumps that perfectly draw a line from them to the prostitute Moll, who, of course, has had the fashion sense—not to mention the integrity—to sport them from the start.

The opera house is a secular cathedral, the audience a congregation, and the communion celebrated by the actors and audience, presided over by a trinity comprised of Author-Director-Conductor. There is no greater transposable story than that. There’s an old saying: “The ink’s not dry until you die.” At the beginning of the rehearsal, Mauceri, dressed in blazer and tie, about to give the opera’s downbeat, rose from his stool and, over his shoulder, drily announced to the production staff, “I’d like to point out that the paint on my stool is wet.” I cannot think of a better metaphor for “free, adult, uncensored” theater. Thanks to this production, I am ready, as a devotee of Blitzstein’s work, to let go of Marc on the piano stool and allow his authorial Authority to grow, to allow the ongoing struggle to reconcile Power, Authority, and Truth to be carried forward through the lens of a conductor’s vision. I encourage everyone else to witness as Blitzstein’s powerful orchestral Cradle at last begins to earn its rightful Authority by catching this production while the paint’s still wet.

This essay has appeared in the Huffington Post. You can read it there by clicking here.

I've also written about Marc Blitzstein here.