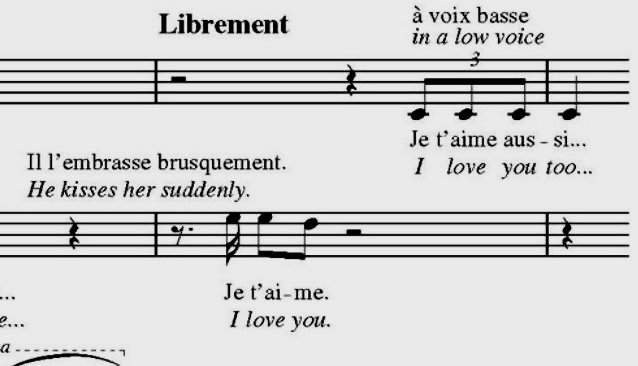

Granted, melody is but one of the strands that make up musical expression; further, what constitutes a beautiful, or even “memorable” tune, is in the ear of the beholder. Factor in that tastes change: we’re always swinging back and forth, pendulum-like, generation to generation, from romanticism to modernism, like drunks sobering up after a binge, staying sober, and relapsing. After Wagner’s hyper-emotional Tristan und Isolde comes Debussy’s emotionally cool Pelléas et Mélisande where most of the frank emotionalism (summoned up by his utilization of all the music elements at his disposal—harmonic and melodic tension and release, dynamics, texture) is in the orchestra and, in an opera about love, “Je t’aime” is sung as though spoken, and in silence.

I recall for two reasons a composition seminar at Juilliard in fall 1985 at which I presented my String Quartet No. 1. Present were our teachers, Milton Babbitt, Elliott Carter, Vincent Persichetti, and David Diamond, as well as about twenty fellow graduate composition students. I remember it primarily because Diamond chewed me out afterwards for “trivializing my work.” I was genuinely surprised by the admonition at the time because I had trusted that the work’s sturdy craftsmanship would speak for itself; that my breezy, self-assured presentation of my musical analysis (I was proud of the fact that every note could be justified both through serial and tonal procedures) would be interpreted as simply unpretentious, and not anti-intellectual. I’m afraid that I never quite embraced David’s advice to “be more respectful of the excellence of your own work in public.”

The second takeaway I recall because it came from an unexpected source. Milton had raised only one point during the question-and-answer portion of the presentation: he had observed that, on the chalkboard behind me, I had mislabeled one of the pitches in my tone row. Chuckling, I had taken no offense, but rather had simply made the correction and sallied into my analysis. Observing my dressing down by the furious Diamond, he came up to me and said, “You know, Daron, it seems to me you pay mightily for that soaring tune in the finale. Maybe ask yourself why.”

I believed then that great talent can and should present itself as “easy.” As an upper-class socialite once asked me in a green room, “Why else would we all call what you musicians do ‘playing’?” Of course, I was not giving our shared labor the respect it deserved, so David was correct. But Milton’s point is the one that stays with me now that age and the years have made David’s advice moot.

The “soaring tune” to which Milton referred had been the third, most “ironed-out” version of the rondo’s fugue subject. I had intended that it trigger something close to what Milton had felt. I had felt it when I wrote it, and I trusted myself enough to commit to it. So there it was, a big wet Dionysian kiss in the middle of my highbrow Apollonian string quartet. Milton knew that it took “courage” to share a good tune, and that the first thing that someone looking to put you in your place does is to call it derivative. Why do I feel even now as though tunes have to be “earned?” Raised Lutheran—and, like many composers of my generation, taught to temper tunes with just enough “abstract” wrong notes to keep them from really taking off—I’ve always wrestled with the “unearned” bliss of unabashed, emotionally-frank lyricism. Early on, during the 90s, a New York Times critic wrote of my first opera that I had “a gift for big, sweeping tunes;” thirty years later, another Times critic thought that my latest opera contained “too much lyricism.” Right.

I thanked Milton for the observation and sort of forgot about the advice that had followed. But, watching my son row with his mates in a shell on the Hudson in the driving rain from the safety of my car this morning, I was reminded that even the bliss of rowing at dawn on the Hudson on a perfect day has got to be earned by also putting out when the weather is inclement.

Back in the day, Ned Rorem’s primly sober Air Music (a terrific piece in which “there’s not a tune you can hum-bum-bum-be-dum,” though there are a couple of really juicy “licks.”) won a Pulitzer, while his Sunday Morning (closer to his heart, more effusively melodic) garnered more love than respect. Some composers might say that it takes more courage to dish out a “big tune” with “soaring horn calls” than it does to craft honorable, abstract pieces just tuneful enough not to rile anyone up. After all, the old conventional wisdom runs, pieces with “good tunes” belong on pops concerts. A highly-tuneful work on a major orchestra’s subscription season can provoke conductorial winks to the audience and players. Diamond accused me of “not enough self-criticism” when what he meant was that I shouldn’t indulge in writing memorable tunes. In Tim Robbins’ Cradle Will Rock gloss, John Cusak, portraying Nelson Rockefeller (in this scenario, the upper class baddie), pours money into abstract art with Sarandon (as the amoral art dealer Sarfatti) on his arm because Rubén Blades’ Rivera (the dangerous artist moving between classes) makes art that riles up working class folks. Cue the Blitzstein. Next on our show: was Modernism a State Department / CIA Psy-Op? I enjoy the off the rails nature of that sort of read, whether it is true or not.

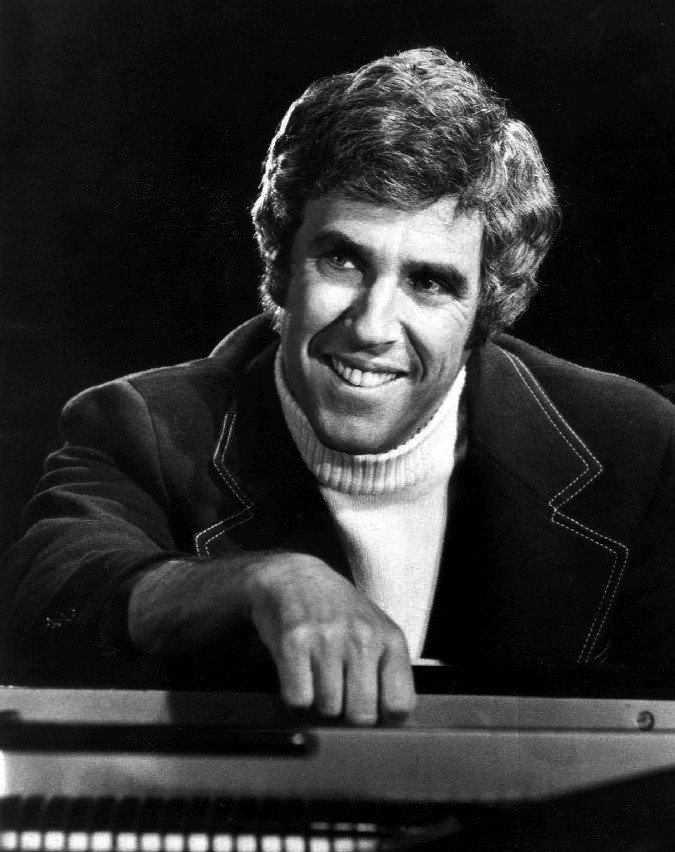

So what’s a tune if you denature it? Parlando. Gian Carlo Menotti pointed out to me once that “recitative and parlando are just foreplay.” I recall attending a performance of Jack Beeson’s opera My Heart’s in the Highlands and growing steadily more irritated that every time he was about to really break out into a memorable tune he cut himself short. Laughing, Bernstein described this affliction as “Tuneus Interruptus.” When Burt Bacharach died, I recalled Babbitt’s advice to “ask myself why” again. Bacharach’s tunes, seemingly bubble-gummy, are actually tricky to sing; it is the composer’s struggle to be both catchy and smart that gives them their zest. The quip that Peter Shaffer puts into Emperor Joseph II’s mouth in Amadeus that there are “too many notes” shifted in the 20th century to something more insidious: now one runs the risk of putting in “too many pretty notes.”

Howard Pollack’s biography of Samuel Barber describes the upper-class Main Line Philadelphia society into which he was born. Ned, born into a middle-class Chicago family, composed increasingly modernist music as he aged. Like Ned, I was born into the middle-American middle-class. Unlike Ned, I found the acquisition of a Mid-Atlantic compositional accent (the whole “abstract” thing where textures and colors take the place of tunes so that other, less confrontational, factors can come to the fore) and the role of arriviste beside the point, as I was steadfastly committed to the pursuit of emotional nakedness, regardless of … “taste.”

The subjective conflation of taste and class is a bit of mischief still managed (even after everything that has happened in the past forty years) by a generation of composers and critics to put down colleagues, and competitors. (The intellectual chauvinism of complacently considering one’s personal taste to be superior to others’ once underpinned entire careers.) Compare and contrast the “middlebrow” way that the music of Richard Strauss, who, in 1947, apparently referred to himself as a first class second rate composer, lands; and the way that Gustav Mahler’s Proto-Modernist internationalist worldview combined Jewish folk music and Christian religious music; and the “highbrow” way that Elliott Carter’s indispensable music lands. While Mahler’s and Strauss’ music is still programmed a century after their deaths, Carter’s music is not despite its excellence, because he didn’t throw any “tuneful” bones to the musically uninitiated.

A still from Humoresque, the lachrymose, under-rated camp classic starring Joan Crawford, Oscar Levant, and James Garfield, whose screenplay by Clifford Odets contained some delicious late-40s social satire.

An artist who labors to conceal his craft is, when successful, often described as an “effortless” melodist and derided as a “tunesmith” rather than as a composer. A “tunesmith” is a tradesman; a composer is an artist. In The Agony and the Ecstacy, novelist Irving Stone has testy Pope Julius shout up to Michelangelo, “When will you make an end?” The maestro snarls back, “When I am finished.” Crawford’s contempt as the dissolute patroness Helen for Garfield’s vulgar “striver” virtuoso violinist Paul in Humoresque, for all the arch camp with which it is presented, is adroitly mixed by someone who had been around and seen a thing or two (playwright Clifford Odets) with envy, self-loathing and lust. Humoresque, the ditty by Antonín Dvořák, was clearly chosen because its a bit of “high class”, "cheap” sentimentality — the sort that works incredibly well in the concert hall. Artists move freely through classes, it is true; but we’re still servants at play; we are meant never, ever to forget who owns the house, and the way to the kitchen door. We’re still talking about how talent intersects with class, aren’t we, Milton? You old fox.

A digression, perhaps, but it is important to mention that it isn’t just “melody” that comes in for the class-related slap down. I recall the casual condescension with which a professionally cosseted colleague whose cultural reference points (and social aspirations) were shaped by their years at Harvard and Columbia dismissed within my hearing the first movement of my Koto Concerto. Why? Because, for them, “serious” meant “saturating the chromatic” and I had, as a compositional challenge, based it entirely on a simple pentatonic pitch group. Consciously or not, because of his allegiance to a musical style that would land best with the gatekeepers from whom he wanted things, he considered poor taste an aesthetic strategy I employed knowingly for effect because I wasn’t speaking to him.

When the American Academy gave me an Academy Award a few years ago, the citation noted that I was being honored for having “achieved my own voice.” Grateful as I was for the recognition, I admit that I was a little puzzled by the citation. Stephen Sondheim’s smart, tart lyric from Anyone Can Whistle came to mind: “What's hard is simple. / What's natural come hard.” I think my songs are harder to sing than they need to be. I’m still —still! — after forty years, struggling to make them “easier” to sing. (Not to mention play: operas with sight-readable vocal scores get programmed more often than complex ones for many reasons — an easy vocal score is a symptom, not a cause.) I still believe that anybody can, in fact, whistle; I believe, as Marc Blitzstein used to famously scrawl, in “peace, justice, and good tunes.”

Why? Because, in the final analysis, good tunes are the surest, most generous, most intimate way a composer has to share unconditional, unearned love with an audience. That’s why tunes move us so deeply; why they threaten some people, console others, and embarrass others. As Milton admonished me so long ago, “Maybe ask yourself why.”