You could be a stranger alone in a foreign city and still find a friendly face to sit next to by locating the little flash of yellow in the audience and heading for it as, onstage, musicians rehearsed. After a quick whispered greeting (no introductions necessary) you could take a seat next to the partitura's holder, who would, without being asked, share it with you -- possibly even place a finger momentarily on the spot being rehearsed to help you get your bearings. By the end of the rehearsal you would have made a new friend -- possibly for life. Rome, New York, Vienna, or Paris -- the city's name and geographic location were irrelevant: you were a musician, an artist, a citizen of the world, and that flash of yellow, that pocket score, was your passport, universally accepted and valued.

John Updike called the (now Knopf) Everyman Classics volumes "the edition of record." Hard to dispute. They were designed to fit in the vent pocket of a man's blazer, there to be found while seated alone in a cafe drinking espresso or absinthe or both one assumes; or drawn out whilst seated on a park bench enjoying a good pipe; or to be drawn like a sword by a physical laborer during his break intent on intellectual self-betterment. One can't rekindle, as it were, a conversation with a book or score begun decades before when reading it on an iPad. And, if one's blessed to have had parents who wrote in the margins of their books, then their conversations can continue with you as you come upon them as you read them; at those times it is as though they had never died.

These thoughts occurred to me yesterday when I drew from the shelf in my studio the yellow Eulenburg edition of Beethoven's Symphony No. 8 to study, as a musician does, prior to rehearsing it last night with the Orchestra Society of Philadelphia. As a composer of concert and theater music in his fifties, one of my passions is the symphonic works of Beethoven and Haydn. As devotedly as I study Verdi as an opera composer, I am deadly serious -- particularly after having composed five symphonies myself -- about improving as a symphonic writer: climbing into Beethoven's skull and physicalizing his musical thinking by conducting it is just the thing.

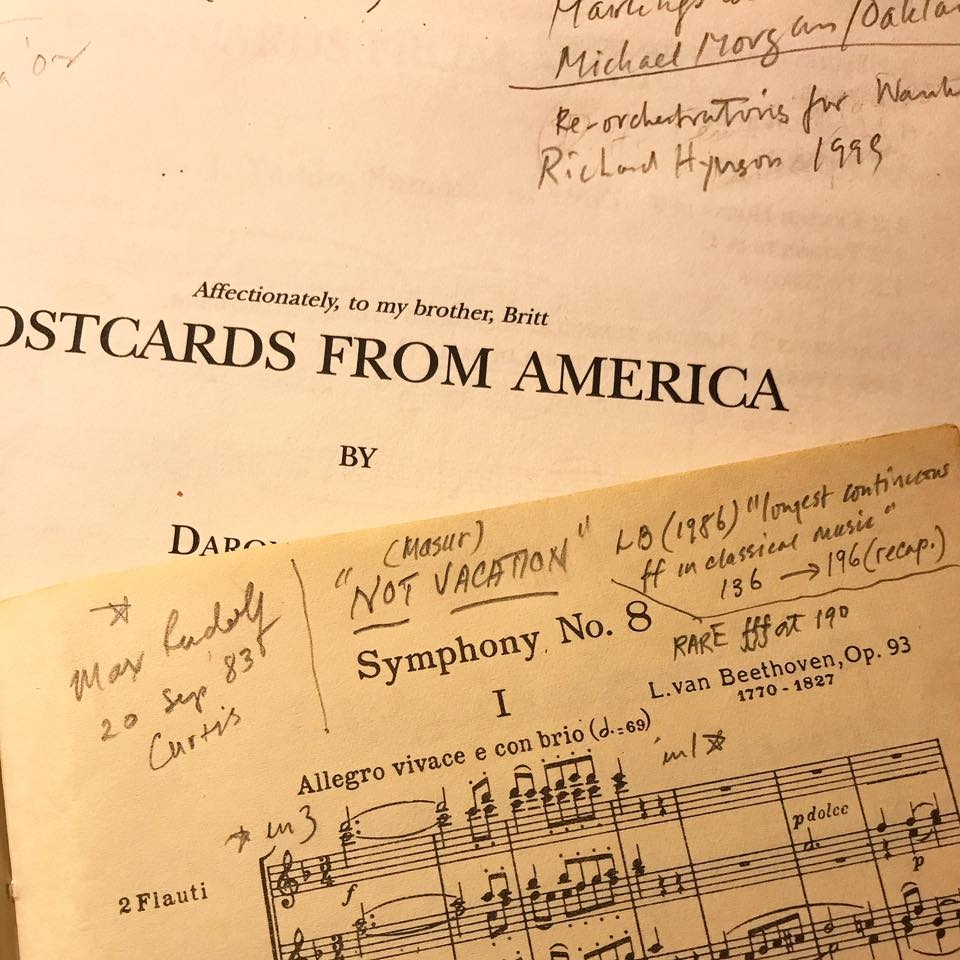

I turned to the first page and was surprised to find, jotted in the upper left hand corner, "Max Rudolf, 20 September '83, Curtis." I'd completely forgotten even attending the rehearsal. Yet, in a sudden rush (like that episode of "Star Trek" where Spock puts on the Smart Guy Helmet) all of the maestro's comments suddenly downloaded from some sort of musical cloud. I paged forward and found notes I'd taken on the use of "piqué," a bowing technique ideal for setting up the entrance of the first movement's second theme. Later, in the Menuetto, "October 10, '83 -- Rudolf takes repeats in the da capo." And so forth.

Returning to the first page, I read, in the upper right hand corner, "LB, 1986 -- 'longest continuous fortissimo in classical music'," from a masterclass Bernstein had given at Tanglewood. "Rare forte-fortissimo at 190," and, later, comments about the "empty" measures in the first movement (bars when nobody plays) pointing out Beethoven's defining of musical structure through negative space (read: silence). Suddenly I recalled the humid Berkshire morning in it's entirety -- me, 25 and hung over, watching the young conductors sweat bullets, my yellow score on my lap, learning.

Returning again to the first page, written above the title, the words "NOT VACATION" in capital letters. Above them, in parentheses, the name Masur. That rehearsal I recalled. Maestro had mentioned to the Philharmonic sometime during his tenure there that Beethoven is said to have finished the 8th while still composing the 7th, the magnificent choral 9th still nascent in his imagination. There was nothing "light" about a piece many call one of the lighter symphonies. My notes above the trio in the Menuetto, for example, note Masur pointing out that the writing clearly foreshadowed Brahms. "It's like he was seeing into the future," I said to the orchestra last night as we rehearsed the section again. "This time, play it like Brahms," I said, "and you'll see!" They did. We did.

I have written often over the years of matrimony -- the many things ("all of the good things," as my father once admitted, without a trace of sentimentality) that my artist mother taught me. I'm acutely sensitive to the concept of "hegemonic masculinity" in music history. It's wrong, from our historic perspective, that women composers' works have been sidelined by the men programming concerts and writing the history books. I've worked to change that during my life in music. I do understand, also, that young composers of all gender identifications are understandably eager to wriggle out from beneath not just their professors' thumbs but from the demands placed upon them by the perceived excellence of prior generations' artistic achievements. The repertoire forces us to come to terms with the troublesome, ultimately inescapable demands of Acquiring Craft, and of Continuous Study. These facts of musical life are, to me, gender non-specific.

I went to sleep last night with Beethoven's music in my muscles, and his way of thinking in my brain, confident, excited by the fact that the study beforehand and the movement during rehearsal, the activity of transforming with my brothers and sisters in the orchestra the master's notes into sound would somehow rewire my own thought processes during the night. I awoke this morning changed -- better, humbler, intensely grateful for the opportunities that a life in music has given me to reconnect with a past that is smarter and wiser than my own. I'm launching at last into a multi-year project to rehearse every Haydn symphony with the orchestra. I am ready to draw his scores from the shelves of my studio and learn.

This piece has also appeared in the Huffington Post. Click here to see it there. Learn more about the Orchestra Society of Philadelphia by clicking here.