This essay is reprinted from the Huffington Post, which published it on 1 September 2015. You can read it there by clicking here.

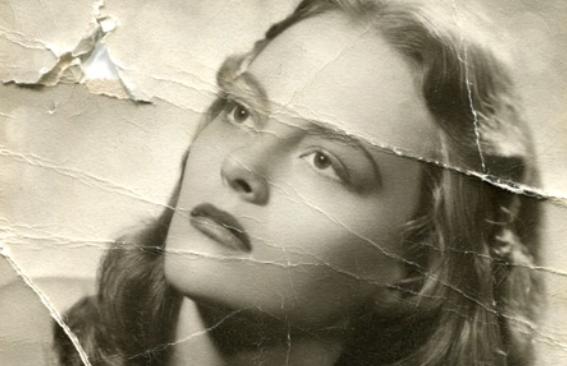

Gwen Hagen, in a publicity still from her years as an actress.

I’m writing a libretto about Orson Welles right now. Searching, as so many have, for Welles’ Rosebud has made me think about my own. So I wrote to a trusted friend and asked him what he thinks has inspired my life’s work. “Loss,” and “endurance,” he replied. “In the true midwestern spirit, living through what comes.”

Not surprisingly for a composer, sound figures centrally in my memories of childhood. At age eight, during the summer of ‘69, one of the most comforting sounds I knew was the sound of Mother’s manual Royal typewriter. The telegraphic patter, a rush of keystrokes followed by the thud of the space bar; the zestful (or pensive, or trepidatious) winding sound followed by a sharp click as she pulled on the return lever and hauled the carriage back to begin a new line. The whirr (or whine, or snarl) as a sheet of paper was pulled out; the stuttering sound as a new sheet was fed to the beast.

I could tell how her work was going just by the sound of her typing. Even when it was going badly (longer pauses, more cigarettes, the sound of her chair as it screeched when she got up to look out the window) it made me feel safe. She nearly always cooked at the same time. For some reason, I remember the smells mostly of cabbage, roast beef, baking bread and stews. She listened to the Paganini violin concerti, one after the next, or the local classical radio station, WFMR or Frank Sinatra singing Cole Porter.

I worked hard not to disturb her, but I was only eight, and, if it was summer, I’d inevitably ask her one too many questions, derail her train of thought and pull her out into the sunshine, where she’d set me a task pulling weeds as she tended her magnificent irises. The hotter the sun beat down, the more intense the smell of the cocoa bean shells that we used to pick up in great sacks for free at the Ambrosia Chocolate Company in the Menominee River Valley and spread on the gardens like mulch. Massive broods of cicadas sang, their husks mixing in with the cocoa bean shells when the nymphs burrowed up out of the ground, moulted and reached maturity.

She was beautiful, and she knew everything. I was her smart son, and I wanted to learn everything. I was adored. I could read just enough to make my way through a few paragraphs now and then. The language was grown up: adult dialogue about being unfaithful, or desperate or simply puzzled. I still recall fragments of stories about handsome young men standing at the screen door, restive wives left on their own with their children and a copy of A Room of One’s Own, moths throwing themselves at flames, and the folly of parenthood. I remember how the stack of manuscript pages grew and disappeared into large manila envelopes, which she sent to magazines in Philadelphia, New York, Los Angeles or Chicago.

That winter, dread-filled, Mother fielded a series of increasingly upsetting telephone-calls from her beloved brother. A sensitive fine artist and chronic alcoholic, Keith had taken commercial work as art director at the Chicago Tribune. During the last, he confessed that he intended to take his life.

I was still too young to be left at home alone. I don’t know where my brothers were. There was no time to get a babysitter. My parents took me with them as they proceeded from one bar to the next, one hotel to the next, in downtown Milwaukee, looking for him. In the end, they found him in a room at the Ambassador Hotel on Wisconsin Avenue. He had washed down a lethal dose of chloral hydrate with vodka.

They emerged, holding hands, from the hotel. It was the single time I saw them touch affectionately. Frightened, I curled up in the back seat wearing my brother’s coonskin hat (Daniel Boone was our favorite television show) and pajamas. I watched through the car window as my distraught parents talked with the police. At that moment, I knew that tragedy had, for the moment at least, made me superfluous. Cold. The blood-clot-red rotating lights of the police car. The wondering why an ambulance was required to convey a dead person.

We drove home. In the front seat, in their own world, my parents spoke in subdued, strained voices. The words were indistinct, but the music was like a transmission heard from far off in space — little vocal jabs, sighs, murmurs and upward queries. Pauses, followed by a tumble of syllables met with another silence. The streetlights came on as we drove west towards the suburbs. The javelin-like flares of light hurtled across the hood of the car as, from under a blanket in the back seat, I watched them pass by overhead.

“Let it go,” I heard Father say to Mother. I listened to the “kuddah-CHUNK, kuddah-CHUNK” tattoo the tires made as they passed over seams in the concrete.

“Just let it go.”

Gwen Hagen at the age of 16.

Crackle of gravel in the driveway. The ticks and sighs of the hot engine as it cooled. The slam of the screen door as Father heaved my uncle’s suitcase into the foyer. He went to the kitchen, sat heavily at the table and poured himself the first of the only three drinks I ever saw him pour in our home. (Our second and third were the night Mother died.) I played with the horse track betting stubs that fell out as Mother, tears running down her cheeks, silently unpacked her brother’s clothes for the last time, throwing away, one by one, his suits, still smelling acridly of booze, aftershave, cigarettes and stale sweat.

As the years went by, Mother continued to write, to sculpt, to raise her children, to cope with her husband. Her rejected manuscripts were returned in big manila envelopes. Not one was accepted. In fifteen years, not one. She had stopped saving the rejection slips when I was twelve.

How quaint, how ridiculous, her return address must have seemed to the clever kids in their early twenties culling submissions to The Saturday Evening Post, Dial, Saturday Review and The New Yorker.

The rejection letters (from the same magazines that I have friends and colleagues published in and working at today) that she used to read, standing in her Midwestern kitchen, surrounded by children, the smell of pot-roast and a self-medicating bipolar husband running to fat, could only have been devastating.

The other day, thinking about Rosebud, I thought not of a burning sled, but of a sheaf of papers being reduced to pulp.

Now, I am a reasonably successful mid-career composer of opera and concert music in a world changing so fast that it would have made Mother’s head spin. She’s long gone, of course. But she’d adore my children; she’d be so proud of them. And of me. She would love my wife, as do I, passionately. I take comfort in that. I do remember, with gratitude, on summer days at our home in Upstate New York, as I compose in the house and my boys, now the age I was then, sing in the backyard with the cicadas as once I did. Does the sound of my composing at the piano, counterpointing their play as once the sound of Mother’s Royal typewriter did mine, move them as once I was moved?

I also remember the summer day in 1976 when I stood in the rain in my swim trunks and watched as Mother dumped everything — her manuscripts, the rejection slips, the pretty letterhead and the Royal typewriter — into a garbage can at the head of our gravel driveway. Last went the clay and the tubes of paint. I stood there, watching the rain make the ink on the pages run, and then turn the paper into pulp.

I think about that rainy day when I sit on a committee judging applications for a prize or commission. How easy it was to dismiss her work, unread; I see it done sometimes by some of the people with whom I serve on panels.

I think about that day when, on occasion, I sit across the table from a smug, careerist, entitled punk with money, a degree and connections.

With fury undiminished by the passage of half a century, I think about Mother walking slowly back into the house and stopping when she saw me moving toward the garbage can, intending I suppose to fish some of the things out.

The fact is, Mother was a good writer. And her work with Mari Sandoz helped her to become an excellent one. But the truth is that that fact may not have been the deciding factor in the end.

“Leave it,” she commanded, her voice tired, and remote. “Let it go.” Rain fell straight down.

“Just let it go.”

###

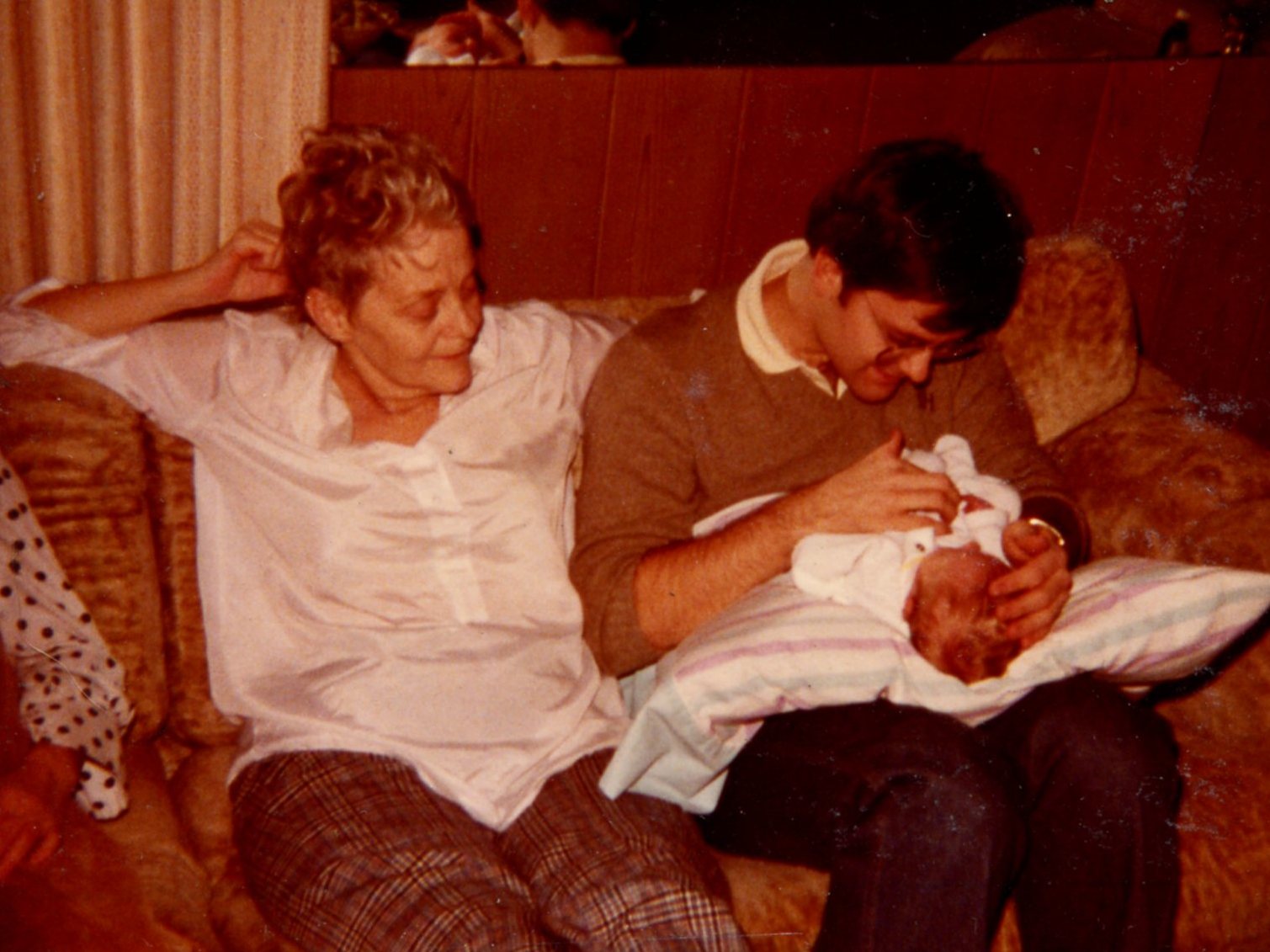

Gwen Hagen with her brother Keith in Milwaukee.

Despite the fact that three act structures are out of fashion these days, my second act—my current career as a composer and my life as a man and father—clearly represents my mother’s third, and final act.

The morning in 1976 after she dumped her dreams of being a fine artist (in the form of her Royal typewriter, art supplies, and manuscripts) in the garbage was a hell of a dramatic act break—a tableaux in which a young mother commanded the son looking on—in whose arms she would in six short years die—to “let it go” as the rain fell straight down and her discarded manuscripts were reduced to pulp.

What became, then, of Gwen Hagen, the “Rosebud” of my article exploring why I compose music, and why the career I have as a composer of concert music and opera has assumed the shape that it does?

Well, the next day she took a job cleaning toilets and changing bedding at a Ramada Inn hotel managed by her brother Garth.

In “My Lost City,” F. Scott Fitzgerald observed that we all live suspended between past and present, and carry the burdens of both. Proust reminds us that when we think we recognize something essential in someone we are, in fact, reaffirming our primal impression of them—an ultimately self-serving exercise that transforms them, in memory, into the person we need them to have been. Accordingly, when I limn the astonishingly quick climb up the “Mad Men” ladder Mother made during her second act, it is not from the point of view of the child I was then but of the man I’ve become.

In truth, money forced Mother to get a job just as it compelled her sensitive visual artist brother to set aside his artistic aspirations to draw women in their underwear as art director for the Chicago Tribune.

Father had left the service and earned a law degree, while fiercely courting Mother. Newly-minted a member of the bar, he had hit the lecture circuit for the American Bar Association, in Mother’s words, “part Atticus Finch, part Clarence Darrow,” admonishing nascent lawyers to remember their ethical responsibilities. He had also hit the bottle.

When he left the Bar Association and entered private practice, our comfortable upper middle class lifestyle collapsed. Although my brothers and I were able to continue to attend the superb Elmbrook schools in which my folks had moved west of Milwaukee to enable us to enroll, our Frank Lloyd Wright-style modernist cedar home, situated at the end of a cul-de-sac (and smack-dab in the middle of a flood plain), became a financial Albatross around my parents’ necks. The dishing of Mother’s artistic ambitions coincided with Father’s return home from Chicago (where he had for years been living weekdays) full time. His sons, whom he disciplined brutally, didn’t like him much.

After a few months changing linens, Mother landed a job at an advertising agency; she began a six-year hopscotch from one employer to another—paste-up artist to copywriter, layout designer to graphic artist, account manager to art director. In time, she landed a job as Art Director at a glossy regional ad-driven magazine called Exclusively Yours.

With Mother in the financial driver’s seat, my brothers and I watched Father gradually corroded by a toxic stew of narcissistic frustration and alcohol. The booze robbed him of moral authority with his children; our increasing size took domination through physical intimidation off the table. We were lost to him. Mother had long been the only reason any of us interacted: she became the only reason we ever interacted at all with Father, whose loopy orbit, as far as we were concerned, was taking him out beyond Pluto.

She was by all accounts great at an incredibly stressful job. She took immense satisfaction in her career. That doesn’t change the fact that, like many children of folks who worked in advertising during the 60s-70s, I find the television series “Mad Men” excruciating to watch. It is, of course, dead spot on. If Father’s drug of choice was alcohol, hers was, alas, physician-prescribed Valium. That, and three packs of Pall Mall cigarettes a day at the office.

Like my brothers, I encouraged Mother to divorce Father. Unfortunately, Wisconsin law at that time made it next to impossible for her to extricate herself financially from him. She was trapped.

I am grateful to her for insisting, whether it was true or not, that she had not remained with Father during my high school years for my sake. I am aware of how fortunate I am to have come to know her for the wise, wry, brilliant woman she was. During those years, she and a treasured High School teacher named Diane Doerfler together molded me in such a way that, to this day, not only do I adhere strictly to the way of “the examined life,” but I still collaborate far more easily with powerful women than with powerful men.

With my mother and nephew Ryan, the morning of the day she died.

Ned Rorem invited me to study with him at the Curtis Institute of Music. I was, for better or worse, securely launched on the coast as a serious composer. Mother engaged a lawyer and prepared at last to leave Father. She even discussed with Ned plans to move to Paris and to begin painting and writing again—a third act!

A month later, five years after the Royal typewriter and the manuscripts went into the garbage, she was diagnosed with lung cancer. A year later, in 1982, she died in my arms. The opera composer in me recognizes that as being one hell of a second act curtain.